Passivefool here:

May 8th was the birthday of Jack Bogle and coincidentally as luck would have it, in this post we talk about one of the core messages that Jack spent his entire life preaching with a missionary zeal. We had also published this tribute to Jack a while ago, do check it out.

Jason Zweig, when asked what he does for a living at a conference, answered”

“Between 50 and 100 times a year, I say the exact same thing in such a way that neither my editors nor my readers will notice I’m repeating myself.”

This is one of those posts where I repeat a very basic tenet of investing that has been utter a quadrillion times over and yet oft-ignored by investors.

I keep saying this over and over again, but I’ll say it once more. In investing, you cannot control the direction of the markets, only Donald Trump and LIC can, you cannot control the returns you get, all you can control are your costs and your behaviour.

In investing, you get what you don’t pay for - Jack Bogle

In the last decade or so, the low-cost indexing revolution has steadily spread across the world. Make no mistake, even though low-cost index funds have firmly become a part of the mainstream investing lexicon, they are a very tiny slice of the overall pie. Contrary to the bullshit narratives, low-cost indexing is neither eating the world, nor a bubble.

2008 was a tipping point for investors and advisors alike. While investors realized that they weren’t exactly getting what they paid for, advisors realized that their value wasn’t exactly in picking the hot stock or fund but rather everything except investment management. Today, thanks to Jack Bogle and Vanguard, US investors and advisors alike have finally realized the importance of costs on their investment outcomes and they have voted with their wallets.

Trillions of dollars have flown from high cost useless active funds and closet active funds into low-cost index funds and ETFs. The revolution Jack Bogle started in 1976, is now sweeping the biggest financial market on the planet.

I get that Indian markets are still immature, underdeveloped or whatever you wanna call them. But the indifference of investors towards investing costs is just shocking. Here’s the direct vs regular breakup by investor type. 86% of the assets are invested in regular plans. This data is for T30 vs B30 cities, but the vast majority of the investors are concentrated there so the data is representative.

Forget indifference, a good chunk of investors are downright oblivious about costs. I was having a chat with an incredibly smart person some time ago, someone I have a deep respect for. He said that as long as you believe in a manager, costs don’t matter. That’s kind of stupid thing to say. I agree to a certain extent that, if a manager is delivering performance, he needs to be paid well, but doesn’t mean you disregard costs completely. There are very few unique mutual funds without alternatives in India. There’s always a better fund at a lower price.

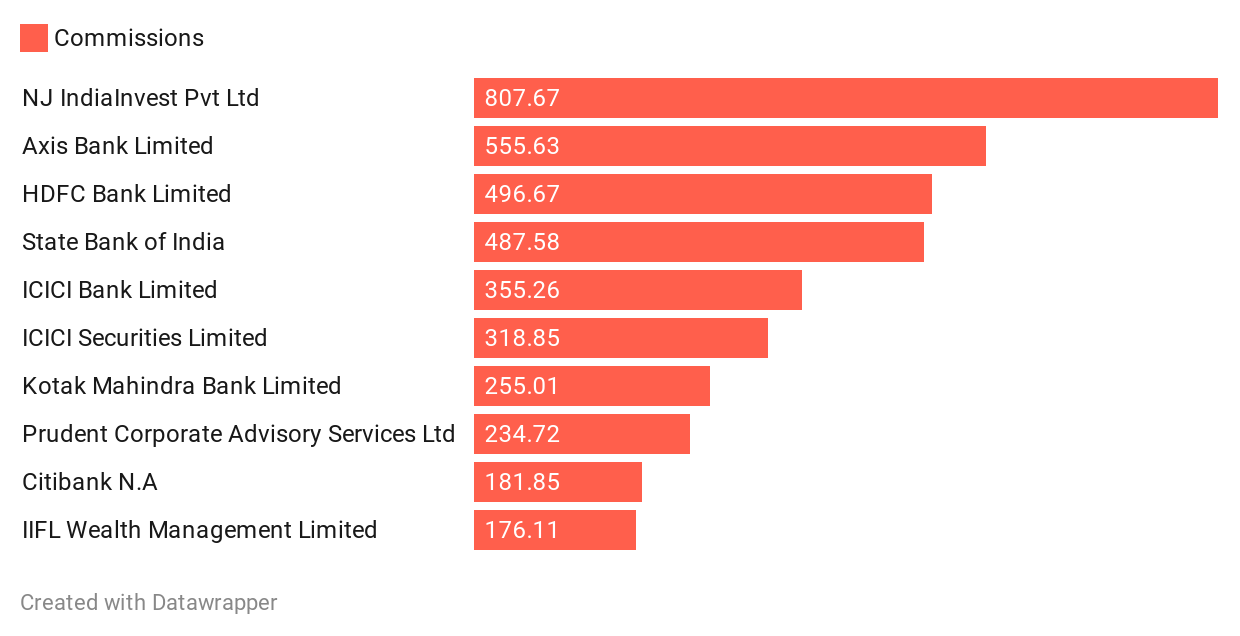

The myopia of investors is just crazy! Don’t get me wrong, I have nothing against regular plans of mutual funds, as long they are used by actual advisors who do more than just recommend a couple of random mutual funds. But the sad reality is that the top 6 distributors by commissions earned are banks. And we all know how deeply banks care about investors and how famous they are for recommending and selling products cleanly.

Today, well over 60-70% of all regular mutual fund investors by my guesstimates are paying commissions for absolutely nothing in return. They are just throwing away money they worked their asses of for.

Why do costs matter?

I’ll let Jack Bogle do the talking here:

The overarching reality is simple: Gross returns in the financial markets minus the costs of financial intermediation equal the net returns actually delivered to investors. Although truly staggering amounts of investment literature have been devoted to the widely understood EMH (the efficient market hypothesis), precious little has been devoted to what I call the CMH (the cost matters hypothesis). To explain the dire odds that investors face in their quest to beat the market, however, we don't need the EMH; we need only the CMH. No matter how efficient or inefficient markets may be, the returns earned by investors as a group must fall short of the market returns by precisely the amount of the aggregate costs they incur. It is the central fact of investing.

The first very first layer of costs you need to be aware of is between direct plans and regular plans of mutual funds. If you aren’t aware, every mutual fund comes in 2 plans - direct and regular. In a regular plan, the AMC pays distributors a commission to sell a fund, which means the regular plan will have a higher expense ratio. Since there are no commissions in direct plans, they are cheaper, which means you get to keep more of your hard-earned money.

This bloody comparison has been made a billion times but I’ll make it once more in the hopes that you guys realize the importance of costs. Here’s how a Rs 10,000 SIP for 20 years with a 10% annual increase in a regular plan of a mutual fund charging 2% and in the direct plan charging 1% would’ve performed. That’s a difference 14,04,705 or 10%. Costs compound slowly and eat into your returns steadily. You can use this handy Freefincal calculator to figure this out.

The second type of costs you need to be aware of are between active mutual funds and index funds and ETFs. I am assuming that if you are reading this you are aware of the difference between active mutual funds and index mutual funds. If aren’t, don’t worry, we got you covered.

The reason why index funds perform well over the long run is because of their cost advantage. The average expense ratio of the regular plans of large-cap active mutual funds is 2.25% while it’s 1.29% for direct plans. It’s 0.46% for regular plans of index funds and 0.30% for direct plans. So, an active fund has to generate a 1.29% (direct) extra return just to meet the benchmark and then generate additional returns over that to beat the benchmark - easier said than done. But index funds, just track the benchmarks, that’s it. And here’s what that means:

Spiva India - Year-End 2019

Over a 10-year period, well over 60% of large-cap funds fail to beat their benchmarks. Meaning, your chance of picking an active fund that can consistently perform is worse than a coin toss. Why in the goddamn hell would you want to choose active mutual funds? It’s a mug’s game. And this not even to mention the other shenanigans the Indian mutual fund industry is notorious for. Hugging benchmarks while charging a high fee, frequently tinkering with expense ratios, not sticking to fund mandates, and 100 other things. But that’s a topic of discussion for 100 other posts because one wouldn’t suffice.

Thanks to one of Jack Bogle’s speeches, I came across a brilliant parable on the importance of costs by Warren Buffett in the 2005 Berkshire shareholders letter. In this parable, Buffett illustrates how the fictional family of Gotrocks, lured by the promise of high returns keep hiring fund managers and consultants, mockingly referred to as “helpers” but they keep making less and less each year because of the fees they paid the helpers. I highly recommend your read the full story but a few excerpts:

And that’s where we are today: A record portion of the earnings that would go in their entirety to owners – if they all just stayed in their rocking chairs – is now going to a swelling army of Helpers. Particularly expensive is the recent pandemic of profit arrangements under which Helpers receive large portions of the winnings when they are smart or lucky, and leave family members with all of the losses – and large fixed fees to boot – when the Helpers are dumb or unlucky (or occasionally crooked).

A sufficient number of arrangements like this – heads, the Helper takes much of the winnings; tails, the Gotrocks lose and pay dearly for the privilege of doing so – may make it more accurate to call the family the Hadrocks. Today, in fact, the family’s frictional costs of all sorts may well amount to 20% of the earnings of American business. In other words, the burden of paying Helpers may cause American equity investors, overall, to earn only 80% or so of what they would earn if they just sat still and listened to no one.

Long ago, Sir Isaac Newton gave us three laws of motion, which were the work of genius. But Sir Isaac’s talents didn’t extend to investing: He lost a bundle in the South Sea Bubble, explaining later, “I can calculate the movement of the stars, but not the madness of men.” If he had not been traumatized by this loss, Sir Isaac might well have gone on to discover the Fourth Law of Motion: For investors as a whole, returns decrease as motion increases.

In the 2018 letter, Buffett further illustrates the pernicious effects of high fees on investment returns:

Nevertheless, in 1942, when I made my purchase, the nation expected post-war growth, a belief that proved to be well-founded. In fact, the nation’s achievements can best be described as breathtaking.

Let’s put numbers to that claim: If my $114.75 had been invested in a no-fee S&P 500 index fund, and all dividends had been reinvested, my stake would have grown to be worth (pre-taxes) $606,811 on January 31, 2019 (the latest data available before the printing of this letter). That is a gain of 5,288 for 1. Meanwhile, a $1 million investment by a tax-free institution of that time – say, a pension fund or college endowment – would have grown to about $5.3 billion.

Let me add one additional calculation that I believe will shock you: If that hypothetical institution had paid only 1% of assets annually to various “helpers,” such as investment managers and consultants, its gain would have been cut in half, to $2.65 billion. That’s what happens over 77 years when the 11.8% annual return actually achieved by the S&P 500 is recalculated at a 10.8% rate.

Costs are like smoking, they’ll kill you slowly, steadily, and silently and by the time you realize what’s happening, it’ll be too late!

This story sums up the penchant for retail investors to de-worseify by chasing fads and shiny new garbage funds. The more I interact with retail investors, the more I am convinced that investors are better off with a single fund in their portfolio and nothing else. Rick Ferri also recently tweeted this, and I agree.

But the problem is we don’t have a balanced index fund in India yet and most of the active hybrid funds are pretty pricy, which defeats the whole purpose of such a fund.

But if you are willing, you can still use a DIY approach and combine a low-cost broad market index fund with a debt fund to essentially create your own low-cost balanced fund. We had written about it here.

Why do active funds fail to beat the benchmarks?

To paraphrase Jack, it’s because of the relentless rules of humble arithmetic.

But whatever returns the stock market is generous enough to deliver in the years ahead, please don't make the mistake of thinking that investors actually earn those returns. To explain why this is the case, we need only to return to that first relentless rule of humble arithmetic that explains the simple mathematics of investing: All investors as a group must necessarily earn precisely the market return, but only before the costs of investing are deducted. After subtracting all the costs of financial intermediation are deducted—all of those management fees, all of those transaction costs, all of those distribution costs, all of those marketing costs, all of those operating costs—the returns of investors must and will and do fall short of the market return by an amount 10 precisely equal to the aggregate amount of those costs. In a market that returns 10 percent, we investors as a group earn 10 percent (Duh!), pay our financial intermediaries, and then pocket whatever remains.

This is of course based on The Arithmetic of Active Management by Nobel laureate William Sharpe:

If "active" and "passive" management styles are defined in sensible ways, it must be the case that

(1) before costs, the return on the average actively managed dollar will equal the return on the average passively managed dollar and

(2) after costs, the return on the average actively managed dollar will be less than the return on the average passively managed dollar

These assertions will hold for any time period. Moreover, they depend only on the laws of addition, subtraction, multiplication and division. Nothing else is required.

Put simply, most active funds charge too much, they have to earn returns to make up for that and then deliver some more to beat the benchmark, which is very very hard if not impossible. Some funds do beat their benchmarks, but your odds of picking them are horrendous.

And then there’s career risk. There are 40 active large-cap mutual funds, if you take a look at their holdings, most of them resemble Nifty 50 or 100. In other words, most active large-cap funds are closet index funds, if all they do is hug benchmarks, how can they outperform? Which means you pay 1-2% for the same thing an index fund does for 0.10%. Doesn’t seem like a very smart thing to do, does it?

Most active funds are 80% beta, 20% bullshit

I was joking when I said this, but it kinda is true.

And the next thing about large-cap funds is that they must invest 80% of the AUM in the top 100 stocks. Which means the only way you can generate outperformance is by significantly deviating from index weights or running concentrated portfolios. If a manager deviates significantly and underperforms the index by too much, his bonus is gone because money will leave his fund. Concentrated portfolios have conviction risk, which cuts both ways, if it works, you’re a star, if not, goodbye bonus. And to be fair, some do run decent focused funds.

And we just started seeing the first mid and small-cap index funds recently. Preliminary evidence shows that active mid-cap funds are having a tough time beating a benchmark like the Nifty Mid-cap 150. It pays to be in an active small-cap fund, but I think small caps are useless for investors.

Ultimately, reaching your goals is what matters, not beating arbitrary benchmarks. It’s better to let the market be your manager and do other worthwhile things in life than trying to pick a hot fund - it’s not possible, it’s not worth it either.

Getting high and watching RGV ki Aag on the other hand, insanely worthwhile!

Introducing the Indexheads podcast

Anish had been thinking of this for a while now but finally, the Investing with Indexheads podcast is now a reality. Do listen to it and let us know your unadulterated ad honest feedback. We have some exciting things planned and we’re just getting started.

Thread bared the nexus and game plan of AMCs, Distributers and CFPs. Going to transfer all my MF investments as meticulously explained in the post.Thanks.

Absolutely brilliant... had no idea costs were eating into the pie at such mind boggling levels... wish newton had discovered the 4th law ages ago... would have saved would be investors a bundle!!! Thanks for sharing this..🙏🏽